The amount of THC in cannabis plants is much higher than 30 years ago

Read MoreStay in the know with the latest on our fight against the legalization of marijuana

Have an article that you would like us to post? Share it on our Facebook page!

Marijuana Is More Dangerous Than Biden’s HHS Lets On→

/In easing restrictions, it brushes past the long-term effects, from anxiety and depression to psychosis.

Read MoreMore Teens Who Use Marijuana Are Suffering From Psychosis→

/More Teens Who Use Marijuana Are Suffering From Psychosis

More potent cannabis and more frequent use are contributing to higher rates of psychosis, especially in young people

Read MoreYou Can Be Addicted to Weed. I Was When I Was 12.→

/Boomers who fought for legalization have no idea how dangerous it is.

Read MoreWhat Happened When Oregon Decriminalized Hard Drugs→

/A bold reform effort hasn’t gone as planned.

Read MoreCannabis industry is poisoning our kids just like tobacco has

/California lawmakers should stop marijuana producers from targeting children with flavored products

Read MoreLegalizing Marijuana Is a Big Mistake

/Of all the ways to win a culture war, the smoothest is to just make the other side seem hopelessly uncool. So it’s been with the march of marijuana legalization: There have been moral arguments about the excesses of the drug war and medical arguments about the potential benefits of pot, but the vibe of the whole debate has pitted the chill against the uptight, the cool against the square, the relaxed future against the Principal Skinners of the past.

As support for legalization has climbed, commanding a two-thirds majority in recent polling, any contrary argument has come to feel a bit futile, and even modest cavils are couched in an apologetic and defensive style. Of course I don’t question the right to get high, but perhaps the pervasive smell of weed in our cities is a bit unfortunate …? I’m not a narc or anything, but maybe New York City doesn’t need quite so many unlicensed pot dealers …?

All of this means that it will take a long time for conventional wisdom to acknowledge the truth that seems readily apparent to squares like me: Marijuana legalization as we’ve done it so far has been a policy failure, a potential social disaster, a clear and evident mistake.

The best version of the square’s case is an essay by Charles Fain Lehman of the Manhattan Institute explaining his evolution from youthful libertarian to grown-up prohibitionist. It will not convince readers who come in with stringently libertarian presuppositions — who believe on high principle that consenting adults should be able to purchase, sell and enjoy almost any substance short of fentanyl and that no second-order social consequence can justify infringing on this right.

But Lehman explains in detail why the second-order effects of marijuana legalization have mostly vindicated the pessimists and skeptics. First, on the criminal justice front, the expectation that legalizing pot would help reduce America’s prison population by clearing out nonviolent offenders was always overdrawn, since marijuana convictions made up a small share of the incarceration rate even at its height. But Lehman argues that there is also no good evidence so far that legalization reduces racially discriminatory patterns of policing and arrests. In his view, cops often use marijuana as a pretext to search someone they suspect of a more serious crime, and they simply substitute some other pretext when the law changes, leaving arrest rates basically unchanged.

So legalization isn’t necessarily striking a great blow against mass incarceration or for racial justice. Nor is it doing great things for public health. There was hope, and some early evidence, that legal pot might substitute for opioid use, but some of the more recent data cuts the other way: A new paper published in The Journal of Health Economics found that “legal medical marijuana, particularly when available through retail dispensaries, is associated with higher opioid mortality.” There are therapeutic benefits to cannabis that justify its availability for prescription, but the evidence of its risks keeps increasing: This month brought a new paper strengthening the link between heavy pot use and the onset of schizophrenia in young men.

And the broad downside risks of marijuana, beyond extreme dangers like schizophrenia, remain as evident as ever: a form of personal degradation, of lost attention and performance and motivation, that isn’t mortally dangerous in the way of heroin but that can damage or derail an awful lot of human lives. Most casual pot smokers won’t have this experience, but the legalization era has seen a sharp increase in the number of noncasual users. Occasional use has risen substantially since 2008, but daily or near-daily use is up much more, with around 16 million Americans, out of more than 50 million users, now suffering from what is termed marijuana use disorder.

In theory, there are technocratic responses to these unfortunate trends. In its ideal form, legalization would be accompanied by effective regulation and taxation, and as Lehman notes, on paper it should be possible to discourage addiction by raising taxes in the legal market, effectively nudging users toward more casual consumption.

In practice, it hasn’t worked that way. Because of all the years of prohibition, a mature and supple illegal marketplace already exists, ready to undercut whatever prices the legal market charges. So to make the legal marketplace successful and amenable to regulation, you would probably need much more enforcement against the illegal marketplace — which is difficult and expensive and, again, obviously uncool, in conflict with the good-vibrations spirit of the legalizers.

Then you have the extreme case of New York, where legal permitting has lagged while untold numbers of illegal shops are doing business unmolested by the police. But even in less-incompetent-seeming states and localities, a similar pattern persists. Lehman cites (and has reviewed) the recent book “Can Legal Weed Win? The Blunt Realities of Cannabis Economics,” by Robin Goldstein and Daniel Sumner, which shows that unlicensed weed can cost as much as 50 percent less than the licensed variety. So the more you tax and regulate legal pot sales, the more you run the risk of having users just switch to the black market — and if you want the licensed market to crowd out the black market instead, you probably need to make legal pot as cheap as possible, which in turn undermines any effort to discourage chronic, life-altering abuse.

Thus policymakers who don’t want so much chronic use and personal degradation have two options. They can set out to design a much more effective (but necessarily expensive, complex and sometimes punitive) system of regulation and enforcement than what exists so far. Or they can reach for the blunt instrument of recriminalization, which Lehman prefers for its simplicity — with medical exceptions still carved out and with the possibility that possession could remain legal and that only production and distribution be prohibited.

I expect legalization to advance much further before either of these alternatives builds significant support. But eventually the culture will recognize that under the banner of personal choice, we’re running a general experiment in exploitation — addicting our more vulnerable neighbors to myriad pleasant-seeming vices, handing our children over to the social media dopamine machine and spreading degradation wherever casinos spring up and weed shops flourish.

With that realization, and only with that realization, will the squares get the hearing they deserve.

Parents are not ready for the new reality of teen cannabis use →

/The voice mail was waiting on Amy’s phone one morning in February 2019, a missed call from her 18-year-old son the night before. When Amy, a mom from Connecticut who is being identified by first name only to protect her family’s privacy, played the message, she heard the panicked voice of her child.

Mom, he said, my face won’t stop twitching. I feel like I’m going to die. I’m trapped in another dimension and I can’t get out.

Terrified, Amy called the campus police at the University of Delaware. They found him asleep in his dorm room. Just a panic attack, they told her.

But she knew better. When she spoke to her son William, who is being identified by his middle name to protect his privacy, he told her: “I’m sorry. I think I just smoked way too much pot.”

Her son — an incredibly bright boy, a rule-abiding kid, a doting big brother — had started experimenting with marijuana as a junior in high school, Amy says. He told her it helped with his social anxiety, which intensified when he went to college, where he started smoking marijuana nearly every day. But the voice mail was the first time William had ever exhibited psychotic symptoms. About two months later, he called again with the same plea for help: He was trapped in another dimension, afraid he was about to die.

“My husband was like, ‘This isn’t from pot, no way, pot wouldn’t do this,’” Amy says. “But I’d started researching cannabis-induced psychosis, and I was like, ‘This is what’s happening.’”

That sense of disbelief — pot wouldn’t do this — is prevalent among parents who have watched their teenagers become gripped by addiction. But the landscape of teen marijuana use has radically transformed in the decades since today’s parents were teens themselves, and many Gen X’ers and millennials might not be attuned to what that means. A typical joint smoked decades ago contained less than 4 percent THC, the psychoactive compound in marijuana that causes the sensation of a high. Dried cannabis flower now averages closer to 15 to 20 percent THC, while the high-potency products most popular with teens — including THC-concentrated oils, edibles, waxes and crystals — often contain anywhere from about 40 percent to upward of 95 percent THC, an astronomical increase in potency that can have a significant impact on a developing adolescent brain.

Meanwhile, the number of American teens using these products has soared in recent years. Research published in 2022 by Oregon Health & Science University found that adolescent cannabis abuse in the United States has increased by about 245 percent since 2000; a 2022 study by the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health found that, in 2020, 35 percent of high school seniors and 44 percent of college students reported using marijuana within the past year. That study also found that vaping was increasing as the most popular method of cannabis use.

Even as more families find themselves navigating the complex new reality of teen cannabis use, an antiquated cultural perception of the drug persists: Marijuana is medicinal, it’s natural, it’s not dangerous.

That’s what Laura Stack thought when her then-14-year-old son, Johnny, told her that he’d tried marijuana at a friend’s party near their home in Colorado in 2014, the same year that marijuana dispensaries first opened in their state. “I said to myself, ‘It’s just weed,’” she says.

She remembers what she told her child at the time: “‘Thank you for telling the truth, but please don’t ever do that again; you’ll ruin your brilliant mind.’” Privately, though, she wasn’t very concerned. “I’d used it when I was in high school, so I said to myself, ‘I used it, I’m fine, it clearly didn’t hurt me,’” she says. “I didn’t have any urgency around it. I was just so ignorant.”

[Potent pot, vulnerable teens trigger concerns in first states to legalize marijuana]

Johnny was a gifted, well-adjusted kid, Stack says, an excellent student with a perfect SAT score in math and a scholarship to Colorado State University. But by the time he was a senior in high school, he’d started vaping and “dabbing” — inhaling high-concentrate THC oil — multiple times per day, and his life unraveled. He developed paranoia, which progressed to psychosis, and he cycled through different treatment programs and hospitalizations as his family frantically tried to help him find a way back to himself. He was ultimately diagnosed with cannabis use disorder and cannabis-induced psychosis; he never tested positive for any other drug. He was put on antipsychotic medication, which helped, until he stopped taking it. In November 2019, Johnny leaped to his death from the top of a parking garage.

Stack has shared her son’s story with high school students and their parents countless times as the founder of Johnny’s Ambassadors, a nonprofit organization that seeks to educate parents and teens about the danger of youth marijuana use. “When we do a parent night or a community event, and I ask a crowd: How many of you know what ‘dabbing’ is? You’ll get just a few hands. And then the ones who raise their hands will say ‘Oh, I thought you meant the dance move,’” she says. “These parents just don’t know. They are just as unaware as I was.”

As an addiction develops, parents often describe a common pattern of decline and disengagement, the distortion of a teenager’s sense of self and personality as they grow removed from things they once cared about. M., a parent in California who is being identified by his middle initial to protect his family’s privacy, watched this happen to his youngest child, S., who is also being identified by his middle initial. S. was a good-natured and affectionate son, his father says, a diligent student and a star athlete who was on track to get a scholarship to a top-tier school; he dreamed of someday going pro.

S. started experimenting with marijuana as a high school sophomore. “He knew his big brother smoked, he knew his big sister did,” M. says. “He was curious. And it’s everywhere. It’s legal, right? It’s natural, right? It’s not meth or heroin.” M. felt he had a handle on what his children were using: “I grew up in the marijuana scene and I smoked weed, I smoked a lot of weed.”

But his son’s product of choice wasn’t the same plant buds that M. once knew; S. gravitated toward cannabis vape cartridges, flavored oils that left no scent in the air, so his parents wouldn’t detect when he was smoking. As his use progressed, fueled in part by his distress over athletic injuries, his behavior began to deteriorate. He grew increasingly hostile when his parents expressed concern. Then, one night in February 2022, S. didn’t show up to a school event, and the police later called to say they’d found him wandering a nearby neighborhood, shirtless in near-freezing weather, consumed by paranoid delusions.

Over the months that followed, M. says, the family endured a succession of traumatic episodes that have left lasting scars: There was the day S. was first hospitalized, when he FaceTimed his older sister in tears and told her that their parents wanted to call the police to take him to the emergency room; M.’s daughter cried as she tried to calm her little brother down, telling him, you need help. There was the second time S. experienced psychotic symptoms, when M. says his son appeared “demonic,” explaining with calm, chilling certainty that his mother had been partially possessed by an evil spirit, and he needed to “kill off” that part of her. There was the time M. was driving his son home, and S. kept begging his father to change lanes repeatedly, because he was convinced that driving behind certain cars would stop his body from itching.

This kind of account represents an extreme outcome — many teens, including S.’s two older siblings, might use marijuana without experiencing anything so severe — but psychotic symptoms themselves are hardly a rarity among adolescents and teens who use marijuana, says Sharon Levy, director of the Adolescent Substance Use and Addiction Program at Boston Children’s Hospital and associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

“I see kids with psychotic symptoms all the time,” she says. “It doesn’t mean they all have psychotic disorders, but it is scary.” In 2018, her team published a letter in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics after surveying more than 500 children during their annual physical exams. Seventy teens who indicated that they had used marijuana “monthly or more” within the past year were asked a follow-up question: Had they experienced a hallucination or paranoia? “These symptoms are really psychotic symptoms,” Levy says, “and 60 percent of these kids said yes, they had experienced one or both of those.”

The impact occurs on a spectrum, Levy says: There are children who might experience hallucinations, delusions or paranoia as an acute symptom that resolves as soon as they’re no longer under the influence. There are teens who experience lingering psychotic symptoms, but can identify them as such — like one of Levy’s recent patients, a teen girl who thought that household objects were talking to her but recognized that this could not be real. And then there are the children like S., who develop psychosis that persists, and who no longer recognize that they are dissociated from reality.

“That’s the most severe form, and that’s the form that happens least commonly,” Levy says, “but I think as you move to lesser degrees of this, it’s actually fairly common.”

Teens are more vulnerable than adults to the impact of THC, Levy says, because the compound affects parts of the brain — the hippocampus, the prefrontal cortex — that are still undergoing structural development during adolescence. THC mimics a class of chemicals that the body naturally produces, Levy says, chemicals that guide the development of neurons in an adolescent brain. “Brain development is a very, very complicated process that we don’t fully understand, but we do know which areas of the brain are really rich in these receptors,” she says. When THC binds to those sites, “it interferes, it messes with the system.”

The lasting impact of this interference has been well documented, Levy says. “We’ve known for a very, very long time that the children who use cannabis products during their adolescence have worse outcomes across the board: They’re less likely to finish school, they’re less likely to get married and start a family of their own, they don’t do as well in the workplace.”

Any psychoactive compound has the potential to be addictive, Levy says, and while it’s true that some people can drink alcohol or use marijuana without developing a substance use disorder, the age of the user and the potency of the product matters: “When it comes to addictive substances, dose matters, and how quickly a dose gets to a brain really matters,” she says. “These highly potent products are much more addictive.”

Recreational cannabis use is illegal for those under age 21 in the U.S., but some studies indicate that children can more easily access the drug in states where it has been legalized. Some parents note that their children first accessed the drug through older friends or siblings who had obtained a medical cannabis card when they turned 18.

“The dramatic rise in adolescent cannabis use in 2017 really does coincide with the wave of decriminalization in the country,” says Adrienne Hughes, lead author of the OHSU study and assistant professor of emergency medicine in the OHSU School of Medicine. Beyond rendering the drug more accessible, she says, legalization has also “contributed to the perception that it’s safe.”

Levy believes the problem isn’t legalization itself, but rather a lack of sufficient regulation (Vermont and Connecticut are the only states to limit the potency of cannabis concentrate products). In certain states, she says, “the industry is very involved in regulating itself … which means that more and more products are available, and there is more confusing messaging to the population.” The result, she says, is that “marijuana is becoming more accepted by parents and kids, and it’s also more dangerous.”

But even for children who have been diagnosed with cannabis-induced psychosis, Levy says, there is hope of recovery; if they stay sober, their brains have the potential to heal.

That is what M. and his family are fiercely hoping for. M. estimates that he’s spent well over $100,000 on hospital and ambulance bills and rehab to try to save his son, who was diagnosed with cannabis use disorder and cannabis-induced psychosis. S. has been in an inpatient recovery center in California for about two months, and he’s doing better, M. says, but he still has months of treatment ahead of him.

There are moments when M. can envision a future for his son again: Maybe S. will attend community college, when he’s ready. Maybe he’ll study a foreign language — S. has sometimes said he’d like to live overseas, to get away from marijuana. “I’ve accepted the fact that he may never play [sports] again,” M. says, “but I really hope he does, because it really anchors him. It centers him. But I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

The rest of the family is still recovering, too. “It’s all so traumatic. We all have PTSD, we all have guilt, we’re all in counseling,” M. says. “This is what this does to a family.”

Amy, the mother from Connecticut, said she watched her son “slowly unravel” during his college years as his marijuana use continued to accelerate, leading to a psychotic break in November 2021. For the next year, William was in and out of emergency rooms, psychiatric wards and treatment centers, she says, a time she describes as all-consuming darkness.

“I was talking to all these doctors all around the state and around the country, all these residential treatment centers,” Amy says. “My purpose in life was to keep him alive until we could get him treatment that stuck.” He was diagnosed with severe cannabis use disorder, and doctors told Amy that his psychotic symptoms could be due either to bipolar disorder or cannabis-induced psychosis — the only way to be certain, they said, was to see if the symptoms abated once he was sober for a prolonged period of time.

Finally, in October, Amy and her husband brought their now 22-year-old son to Florida, where he is receiving treatment at an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Amy and her husband are staying with relatives nearby; Amy promised her son she’d stay close, that she’d wait for him to get better.

“They say that for the brain to heal, it literally could take a full year,” she says. “His improvement is vast, but he has a long way to go still.”

In the three years since Johnny Stack died, Laura Stack has seen the demand for her presentations grow. There are now more than 10,000 parent ambassadors affiliated with her nonprofit, she says, and a support group for parents of teens with cannabis-induced psychosis has grown to more than 500 members. She has become adept at reciting the latest research and the most startling statistics. She has learned what to share and what to say to help steer young lives in a safer direction.

But when she reflects on her own story, there are still questions she isn’t sure how to answer. Would it have mattered if they hadn’t lived in a place where it was so easy for her son to access these products? “But it’s everywhere,” she says, “so it really doesn’t matter where you live.” Then she wavers: “I don’t know, though. I wish I had moved.” She is quiet for a moment. “What I know,” she says, “is I would have done anything.”

The legalized drug crisis is harming young people far more than most realize→

/The data is in and it’s becoming increasingly clear that the impacts of commercial marijuana industry are even worse than we thought, particularly for America’s young people. A new report released by Smart Approaches to Marijuana shows the reality in "pot-legal states" paints a vastly different picture than the common sales pitch of the industry and supporters of legalization.

The marijuana industry, which spent billions to lobby elected officials and bankroll legalization referendum campaigns, is following the playbook pioneered by Big Tobacco. They recognize that the road to big profits runs through the heaviest users. As such, they have increased potency of the drug by more than four times since 1998, hoping to hook kids while they are young and vulnerable. The numbers show that it’s working.

Usage rates have reached record highs among those who are most vulnerable to marijuana’s long-term health effects. The National Institute on Drug Abuse warned, "Past-year, past-month, and daily marijuana use (use on 20 or more occasions in the past 30 days) reached the highest levels ever recorded" among those aged 19 to 30. The percentage of 8th, 10th and 12th graders who used marijuana daily has more than tripled between 1991 and 2020.

Daily marijuana use is indicative of a marijuana use disorder, also known as addiction to marijuana. For all the talk about how pot is not addictive, in 2021, 1.3 million individuals between the ages of 12 and 17 had a marijuana use disorder, accounting for more than 46% of users in that age group. Legalization is also associated with a 25% increase in marijuana use disorder among them as well.

Jeremy Baldwin tags young cannabis plants at a marijuana farm operated by Greenlight, Oct. 31, 2022, in Grandview, Mo. Voters in North Dakota and Arkansas have rejected measures to legalize marijuana, while those in Maryland have approved legalization. Similar measures also were on the ballot in Missouri and South Dakota. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel, File)

As usage rates, potency and addiction have increased, the adverse effects have also increased. Though supporters of legalization like to downplay the risks of marijuana, the drug caused more than 70,000 individuals younger than 18 to have marijuana-related emergency department visits in 2021.

The industry told parents and politicians that they would not target kids. That’s turned out to be false. From "Pot Tarts" to "Stoney Patch Kids," the packaging of edibles laced with high-potency THC often looks like traditional snacks. Not surprisingly, between 2017 and 2021, there was a 1,375% increase in at-home exposures to marijuana edibles involving children younger than 6.

More minors are driving under the influence of marijuana too. In 2021, 10.67 million people admitted to driving under the influence of marijuana, including 1.36 million who were between the ages of 16 and 20. There were 2.41 times more minors on the road under the influence of marijuana than were under the influence of alcohol.

Minors have also gravitated toward marijuana vapes, products engineered to include a near-pure form of THC. Between 2017 and 2020, the percentage of 12th graders who vaped marijuana increased from 9.5% to 22.1%. Among 10th graders, it increased from 8.1% to 19.1%, and among 8th graders, it increased from 3.0% to 8.1%. A 2022 study found, "cannabis vaping is increasing as the most popular method of cannabis delivery among adolescents in the United States." and frequent use is increasing faster than occasional use.

The marketing scheme of the industry has been to engineer a more potent drug, in forms easier to consume and while stoking the perception that it’s harmless. In 1991, 78.6% of 12th graders believed that using marijuana regularly puts one’s health at great risk. But in 2021, only 21.6% held this viewpoint. Those who hold that point of view are six times more likely to use it than individuals who perceive it as being high risk.

By 2021 nearly seven in 10 12th graders seemingly approve of marijuana use.

We all want the best future for our children. Yet, the growth of the pot industry has provided kids with greater access to a drug that medical science links to psychosis, depression, suicidality, and lower IQ at a time when the brain is still developing. Regular users are nearly five times more likely to develop a psychotic disorder and users of high-potency marijuana are four times more likely than users of low-potency products to become addicted.

More young people are becoming addicted to marijuana, and it is sending more of them to the hospital. More of them are using a more potent form of the drug. It is past time for our nation to reverse course and advance drug policies that protect our children, rather than allow them to be collateral damage for another Big Tobacco.

How Do You Know if You’re Addicted to Weed?→

/Nearly 6 percent of American teens and adults have cannabis use disorder.

Read MoreGoing Green: The Physical, Mental, And Emotional Problems Associated With Marijuana→

/Although scientific studies indicate that marijuana is associated with profound mental illnesses, emotional problems, and physical diseases, a shocking number of Americans believe that weed is harmless or helpful — possibly even a natural cure for cancer.

Read MorePsychosis, Addiction, Chronic Vomiting: As Weed Becomes More Potent, Teens Are Getting Sick→

/With THC levels close to 100 percent, today’s cannabis products are making some teenagers highly dependent and dangerously ill.

Read MoreCannabis and the Violent Crime Surge→

/Heavy marijuana use among youths is leading to more addiction and antisocial behavior.

Read MoreThe link between drugs, terrorism and mental illness→

/Rod Liddle once actually said to me the immortal words ‘You were right and I was wrong’ at a Spectator summer party. This is a moment I shall treasure till the hour of my death. But even so, I was disappointed. For the subject was only Theresa May. I had predicted she would be a terrible premier. Rod had believed she would be good at the job. A year later, it was obvious who was correct. For one brief shining moment I had hoped that Rod had changed his mind about something much more important. I wish he and a lot of conservatives would shift their opinions about the role of mental illness in rampage killing all over the world. And, once they have done that, I wish they would be willing to examine the role of certain illegal and legal drugs in creating such mental illness.

The trouble with such killings, on both sides of the Atlantic, is that so many people have stakes in attributing or denying blame for them. Those who believe that marijuana is harmless dislike it when I draw attention to just how many such killers (about 90 per cent of them, from Lee Rigby’s killers in London to those responsible for carnage in Nice and Sousse) have been using that drug. The ‘steroid community’ is also highly sensitive about suggestions that these chemicals might be associated with serious violence. But the Norway mass-murderer Anders Breivik, the perpetrator of the New Zealand mosque massacre Brenton Tarrant, the Orlando mass killer Omar Mateen and the London Bridge killers in this country were all steroid users. So was the unquestionably unpolitical rampage killer Raoul Moat, who brought terror to Northumbria in 2010 before killing himself. As for antidepressants, anyone who suggests that these medications may be less than perfect, or that they have unintended consequences, faces a howl of fury from those who take them, and the immense power of the companies which make them.

The trouble with mass killings is that so many people have stakes in attributing or denying blame for them

In the USA, gun-control campaigners want to blame such murders solely on lax gun laws, so they can tighten those laws. In Europe, where most nations think they have guns firmly under control, conservatives like to pin the blame on Islamists. And left-wingers, for comparable reasons, like to implicate ‘right wing extremism’ wherever they can, as it is a problem they are anxious to emphasise.

Well, I think the whole point of journalists is to resist the influence of lobbies and factions of this kind. As a former fanatic and follower of the homicidal creed of Bolshevism I did nothing more violent than the occasional rowdy demonstration. I tend to think that you need much more than a fanatical ideology to cross the well-defined frontier beyond which you might be ready to use gun, knife or bomb against soft defenceless flesh. You may point in reply to the chilly, clear-headed murders and torture done by the Provisional IRA. These were very cruel men. But they were wickedly rational and they wanted to live to enjoy the fruits of their victory. They did not cry out slogans as they killed. They were seldom caught. They were extremely good at covering their tracks and avoiding capture. One of their main aims was to secure an amnesty for those of their number who were imprisoned. And how right they were to assume that their atrocities would eventually force the British government to give way.

But the wild killings of which I write are not like that. In last week’s Spectator, Rod, writing about Thomas Mair, killer of Jo Cox MP, declared that ‘nobody suggested Mair was simply mad’. Well, he was wrong about that. I did. Both at the time of Jo Cox’s murder and later, I repeatedly cited evidence that Mair, a man who washed himself with Brillo pads, was significantly unhinged. Though Mair’s trial weirdly did not consider this aspect of his life, there is a good deal of circumstantial evidence that Mair had been mentally unwell and had probably been prescribed mind-altering medication. His crime was utterly irrational. If Mair had a political cause, as Rod and the British liberal establishment both believe, then he did that cause terrible harm by killing a beloved young wife and mother. He would have had to have been very stupid, or irrational, not to have known that. What sort of political motivation impels a person to damage his own cause?

The next thing I have to contend with, in making this case, is the claim that I am somehow trying to exonerate these killers. I have no such aim or desire. It may be that some of them are better being confined for life in secure hospitals than in prisons, but I want them to be locked up as much as anyone else and more than most. In any given year in this country there are random killings of innocent people by total strangers. The number of these ghastly tragedies varies quite widely but is generally at least in double figures. This is a highly sensitive subject and those who raise it can nowadays expect to be accused of stigmatising the mentally ill. Once again, this is not my aim. I long for our country to provide the mentally ill with the residential hospital care so many of them badly need. I just seek a reasoned and effective response to what seems to me to be a new and unexamined danger.

The facts about these events are often quite difficult to establish. Sometimes they emerge long afterwards. For example, coverage of the 2018 massacre at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida made almost no mention of cannabis or medication. But it is now clear that the culprit, Nikolas Cruz, was a heavy user of cannabis or why else did he say at his trial last week that the United States would ‘do better if everyone would stop smoking marijuana’? He should know.

I only ask one thing from Rod, and from everybody else. It is that the past drug use of every person convicted of a violent crime should be properly investigated, to see if there is, as I suspect, a meaningful correlation between the two. And we should grasp that crazy people often adopt political causes to dignify themselves, but they are still crazy. Never forget that the supposed Islamist Muhaydin Mire, another heavy marijuana user who went berserk with a knife at Leytonstone Tube station, genuinely and literally believed that Anthony Blair was his guardian angel.

Copycat pot edibles that look like candy are poisoning kids, doctors say→

/Dr. Jane Pegg couldn't believe her eyes when she saw the pot edibles that had poisoned a two-year-old who had been rushed to the emergency room in October.

"It so shocked and appalled me … the package looked almost identical to gummies that are sold as candies in the store," the Nanaimo, B.C., pediatrician said.

Read MoreAnother sad story of loss brought to us by the marijuana industry.

/By Aubree Adams

I absolutely loved living in Colorado.

Family-oriented Pueblo is the state’s best-kept secret. Lake Pueblo, Pueblo Mountain Park, and Devil’s Canyon are perfect places to hike. We lived in an old Craftsman home in the historic district, with a beautiful garden and wonderful neighbors. I felt like I was living in a dream.

And then legalized marijuana came, and everything changed. It’s taken nearly a decade for Colorado’s elected leaders to understand the damage pot is doing to our children. I saw it years ago.

My eldest son entered eighth grade in 2014, the year recreational marijuana stores opened in Colorado. Soon, his behavior changed. He became irrational and repeated things that didn’t make sense. I dismissed it as adolescent mood swings. He’d just broken up with a girlfriend. That’s all it was, I told myself.

By his freshman year, I realized he was using marijuana. I was still in denial, though, until he attacked his younger brother and then tried to kill himself. The hospital treated him and sent him home. A few days later, when it was clear he was still suicidal, I took him back to the emergency room. Don’t worry, they told me. It’s just marijuana.

Marijuana is a serious drug

Eventually, my son told me he was dabbing, which I had never heard of. A dab (or wax or shatter) is a highly concentrated form of THC, marijuana’s active ingredient. It’s heated and smoked, delivering an instant, overwhelming high. Crack weed, my son called it. He knew it was making him crazy. He wanted to quit, but addiction had him firmly in its grip.

And yes, he was addicted. Addiction is a pediatric disease. In 9 out of 10 cases, it originates with drug or alcohol use before age 21. Marijuana, which has been linked to mental illness and psychosis in teens and young adults, slowly takes away your humanity. That’s what it did to my son, who turned to running the streets with homeless people. He had no trouble finding people to feed his addiction in return for selling their legally home-grown marijuana.

I quit working, making it my full-time job to save my son. I soon found out that getting treatment wasn’t easy. Beds were full. Officials minimized marijuana's addictiveness.

I found a highly regarded treatment center in Utah; they required $36,000 up front that I didn't have. Finally, I found a place in San Diego that helped restore his health. He regained confidence and looked good. In the meantime, I had learned about a recovery community in Houston, where host families provide positive peer support. My son got better when he left Colorado, so I moved him there in 2016. My other son, who had developed post-traumatic stress disorder, and I followed in 2018.

Rein in this monster

Sadly, my story isn’t unique. Families across Colorado have experienced the same heartbreak and worse. More and more, marijuana is implicated in teen suicides. From 2014 to 2018, marijuana was present in nearly one-third of teen suicides. Pot is taking our children from us.

That’s why a bipartisan legislature this year passed a bill that begins to rein in this monster. The bill:

► Authorizes a study on the effects of high-potency THC products on the developing brain and how to keep those products away from teens. These unbiased experts will make a recommendation for next steps to the legislature.

► Requires doctors issuing medical marijuana recommendations to consider the person's mental health history;

► Orders a report on hospital discharge data when marijuana use is likely;

► Directs coroners to screen for THC in non-natural deaths;

► Reduces the amount an 18-year-old medical card user can purchase in a single day. This closes a loophole that could be exploited to stock up on marijuana concentrates, which they sell to their younger friends.

It’s a baby step, but it’s significant that the state that pioneered marijuana legalization is finally recognizing there are harmful consequences.

We can’t keep going down this road. We can’t keep sacrificing our children on the altar of pot. Big Marijuana promotes high-potency, addictive concentrates with no proof they are safe for anyone. Colorado’s commission, when it reviews all the research already done, will confirm that this product is dangerous to children and much too easy for them to get.

Maybe lives will be saved. Maybe other states will be warned against following Colorado’s lead Maybe no more families will have to endure the hell that mine has.

But it comes too late for me and my oldest son. He started using again. I haven’t seen him in a year.

Aubree Adams is director of Every Brain Matters. She is the parent coordinator for a Houston recovery community, where she lives with her youngest son and two dogs.

Are scientists missing the forest for the trees on youth marijuana use?→

/Are scientists missing the forest for the trees?

Last week, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a study by DM Anderson and colleagues, scientists from universities in Montana, Spain, and San Diego, California. The study finds that legalization does not increase adolescent marijuana use. The researchers analyzed the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began conducting in 1991.

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)

YRBSS collects data from high school students every two years about behaviors that contribute to unintentional injuries and violence, sexual behaviors related to unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, alcohol and other drug use, tobacco use, unhealthy dietary behaviors, and inadequate physical activity. Not all states participate in YRBSS, and those that do participate periodically, although in the 2019 YRBSS all but five states did so. Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington State have never participated in YRBSS. The survey asks three questions about marijuana: ever use, current use, and what age students were when they started using marijuana. It began asking about vapor product use in 2015, but never asks what students are vaping.

So far as these limited data are concerned, the researchers’ findings seem true. But two other national surveys show us something more.

The National Survey on Drug Abuse/National Survey on Drug Use and Health

The National Survey on Drug Abuse is the oldest. It began in 1971 and was financed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Its first two surveys were done under the auspices of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse. It began publishing annual data in 1976 and was transferred to the newly created Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in 1992. Technological innovations enabled the survey to be redesigned in 1999 and its name was changed to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) in 2002. However, the redesign of the renamed survey resulted in an inability to compare its results with findings from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse.

The NSDUH collects data annually on the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs from adolescents (ages 12-17), young adults (ages 18-25), and older adults (ages 26 and older). It combines two years of data to report drug use among these age groups by state but unfortunately not before 2002. RTI is the contractor responsible for administering this survey, which also collect data on the mental health of Americans.

Monitoring the Future (MTF)

The third national survey is Monitoring the Future (MTF), which began in 1975. Financed by NIDA, MTF is the only survey that can give us continuous data from 1976 through today. It collects data about the lifetime, past-year, past-month, and daily use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drug by students in grade 12. It added students in grades 8 and 10 in 1990. In 2015, MTF began asking about vaping and two years later asked specifically what kids were vaping – nicotine, marijuana, or just flavoring. Unfortunately, it does not report its data by state. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research administers this survey.

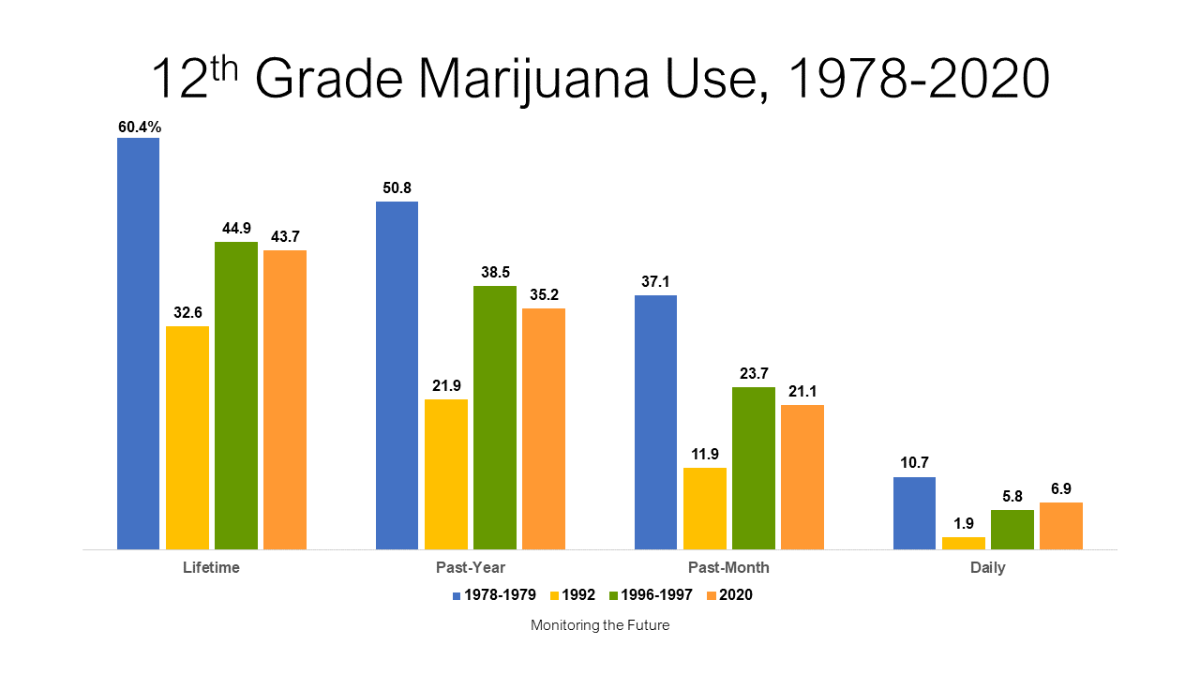

The chart above shows that drug use among high school seniors peaked in 1978-1979. A 1977 study called Highlights from the National Survey on Drug Abuse estimates that in 1962, less than 2 percent of the US population and less than 1 percent of adolescents had ever tried an illicit drug. Over the next 16 years, “ever-tried” use rose among seniors to 60.4 percent, while 50.8 percent of seniors used the drug in the past year, 37.1 percent used it in the past month, and 10.7 percent used it daily. What drove that astonishing escalation in use among 18-year-olds?

Decriminalization and Drug Paraphernalia

The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) formed in the early 70s and initiated a movement to decriminalize marijuana. Decriminalization then was defined as reducing criminal penalties for possessing an ounce or less of marijuana, enough for personal use. In 1973, NORML persuaded Oregon to decriminalize marijuana and in rapid succession over the next five years,10 more states decriminalized. By 1978, eleven states had reduced marijuana penalties to that of a traffic ticket. Along with decriminalization emerged the drug paraphernalia industry called by some “little learning centers for young drug abusers.” Head shops (shops for “heads” as the industry called drug users) selling child-appealing toys and gadgets to enhance drug use opened in urban and suburban communities across the US throughout the 70s, leaving no doubt in parents’ minds that a drug paraphernalia industry was coming after their kids. Studies showed that children reasoned a government would not reduce penalties for a drug that could hurt them.

The Parent Movement

This gave rise to a national Parent Movement which began in Atlanta in 1976 and spread across the nation. The movement was based on three goals: join with other parents to protect kids from becoming drug users, shut down headshops, and stop decriminalization. Some 3,000 parent groups from the mid-70s to the early 90s formed parent peer groups to protect their children and their children’s friends from using drugs. Many, usually in state capitals, became politically active. Their efforts to persuade legislators to pass laws outlawing drug paraphernalia drove the industry out of business. No more states decriminalized marijuana over the next several decades. NORML’s funding nosedived forcing the organization to severely curtail its decriminalization crusade.

Between 1978-79 and 1992, high school seniors’ marijuana use plummeted:

Lifetime use was cut nearly in half from 60.4 percent to 32.6 percent.

Past-year use dropped by more than half from 50.8 percent to 21.9 percent.

There was a three-fold decrease in past-month use, and a

five-fold decrease in daily marijuana use.

The first two directors of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Robert DuPont, MD, and William Pollin, MD, credit the Parent Movement with bringing about this significant reduction in marijuana use among adolescents. But in just four years, these gains reversed:

Seniors’ lifetime marijuana use rose from 32.6 percent in 1992 to 44.8 percent in 1996-1997.

Their past-year use nearly doubled over those four years, from 21.9 percent to 38.5 percent.

Past-month use among seniors did double, and

Daily use rose more than three-fold.

What made that happen?

Medical Marijuana

In 1992, three billionaires began pumping money into a by-then moribund NORML as well as into two new groups, the Marijuana Policy Project, and a coalition of other groups that became the Drug Policy Foundation. They targeted states that allow ballot initiatives, made unsubstantiated claims about the healing powers of marijuana, bought voters’ signatures, and placed measures to legalize marijuana as medicine on the ballots of states few lived in, leaving taxpayers to pay for the consequences of their actions. A steady stream of media stories across the nation educated children that pot is medicine and they responded in kind. If a government wouldn’t reduce penalties for a drug that could hurt you, that drug surely couldn’t hurt you if it was medicine! The national cacophony that led up to the first state legalizing pot as medicine – California in November 1996 – carried that message and kids heard it loud and clear.

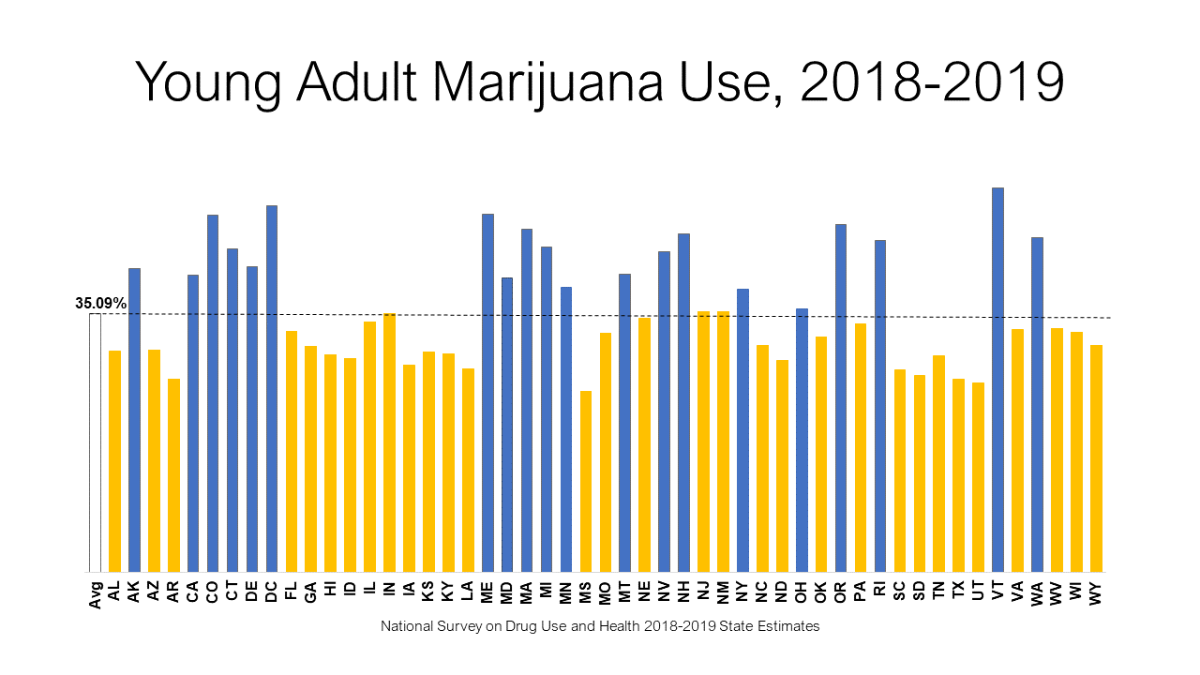

The National Household Survey on Drug Abuse shows much of these same patterns for both adolescents and young adults during the 70s, 80s, and 90s. But since that survey’s data cannot be compared to NSDUH’s, the best we can do is look at the most recent survey, which is the 2018-2019 state estimates. The following two charts are created on the same vertical axis of 0 percent to 60 percent. The first one shows past-year marijuana use among adolescents, the second among young adults.

No, not all of the blue bars are recreational states and yes, some of the yellow bars are. But 36 of these states have legalized marijuana for medical use and that has influenced young people ages 12 to 25 to engage in its use. Like decriminalization in the 70s, the novelty of turning pot into medicine with an intensive four-year campaign championed by national media has not only had a profound effect on the nation’s young people but also introduced a unique way to approve medicines by ballot-iinitiative and, later, legislative fiat rather than through the Food and Drug Administration. Should we worry that advocates are now applying that pattern to other drugs?

Access these graphics here.

Access YRBSS here.

Access NSDUH here.

Access MTF here.

Read National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of Methodological Studies, 1971-2014 [Internet] here.

UCSD Study: Dispensaries Lack Adequate Screening to Keep Out Minors→

/California prohibits children from cannabis dispensaries and shields them from cannabis marketing, but those statewide restrictions are not working as well as policymakers had hoped, according to a UC San Diego–USC study released Tuesday.

Read MoreDoes marijuana legalization work? The answer is a resounding No.→

/In a powerful review of how Colorado is doing since legalizing marijuana for medical use in 2009 and for recreational use in 2014, David Murray of the Hudson Institute suggests the answer is a resounding “No.”

Read More