Are scientists missing the forest for the trees?

Last week, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a study by DM Anderson and colleagues, scientists from universities in Montana, Spain, and San Diego, California. The study finds that legalization does not increase adolescent marijuana use. The researchers analyzed the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began conducting in 1991.

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)

YRBSS collects data from high school students every two years about behaviors that contribute to unintentional injuries and violence, sexual behaviors related to unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, alcohol and other drug use, tobacco use, unhealthy dietary behaviors, and inadequate physical activity. Not all states participate in YRBSS, and those that do participate periodically, although in the 2019 YRBSS all but five states did so. Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington State have never participated in YRBSS. The survey asks three questions about marijuana: ever use, current use, and what age students were when they started using marijuana. It began asking about vapor product use in 2015, but never asks what students are vaping.

So far as these limited data are concerned, the researchers’ findings seem true. But two other national surveys show us something more.

The National Survey on Drug Abuse/National Survey on Drug Use and Health

The National Survey on Drug Abuse is the oldest. It began in 1971 and was financed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Its first two surveys were done under the auspices of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse. It began publishing annual data in 1976 and was transferred to the newly created Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in 1992. Technological innovations enabled the survey to be redesigned in 1999 and its name was changed to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) in 2002. However, the redesign of the renamed survey resulted in an inability to compare its results with findings from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse.

The NSDUH collects data annually on the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs from adolescents (ages 12-17), young adults (ages 18-25), and older adults (ages 26 and older). It combines two years of data to report drug use among these age groups by state but unfortunately not before 2002. RTI is the contractor responsible for administering this survey, which also collect data on the mental health of Americans.

Monitoring the Future (MTF)

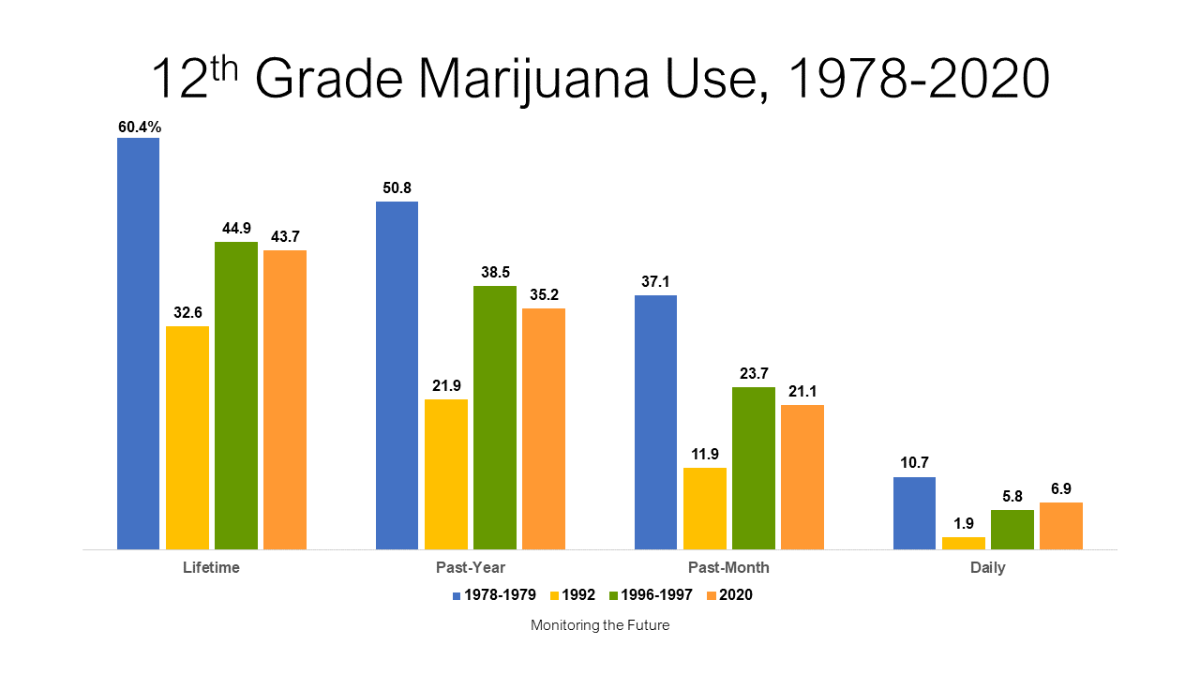

The third national survey is Monitoring the Future (MTF), which began in 1975. Financed by NIDA, MTF is the only survey that can give us continuous data from 1976 through today. It collects data about the lifetime, past-year, past-month, and daily use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drug by students in grade 12. It added students in grades 8 and 10 in 1990. In 2015, MTF began asking about vaping and two years later asked specifically what kids were vaping – nicotine, marijuana, or just flavoring. Unfortunately, it does not report its data by state. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research administers this survey.

The chart above shows that drug use among high school seniors peaked in 1978-1979. A 1977 study called Highlights from the National Survey on Drug Abuse estimates that in 1962, less than 2 percent of the US population and less than 1 percent of adolescents had ever tried an illicit drug. Over the next 16 years, “ever-tried” use rose among seniors to 60.4 percent, while 50.8 percent of seniors used the drug in the past year, 37.1 percent used it in the past month, and 10.7 percent used it daily. What drove that astonishing escalation in use among 18-year-olds?

Decriminalization and Drug Paraphernalia

The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) formed in the early 70s and initiated a movement to decriminalize marijuana. Decriminalization then was defined as reducing criminal penalties for possessing an ounce or less of marijuana, enough for personal use. In 1973, NORML persuaded Oregon to decriminalize marijuana and in rapid succession over the next five years,10 more states decriminalized. By 1978, eleven states had reduced marijuana penalties to that of a traffic ticket. Along with decriminalization emerged the drug paraphernalia industry called by some “little learning centers for young drug abusers.” Head shops (shops for “heads” as the industry called drug users) selling child-appealing toys and gadgets to enhance drug use opened in urban and suburban communities across the US throughout the 70s, leaving no doubt in parents’ minds that a drug paraphernalia industry was coming after their kids. Studies showed that children reasoned a government would not reduce penalties for a drug that could hurt them.

The Parent Movement

This gave rise to a national Parent Movement which began in Atlanta in 1976 and spread across the nation. The movement was based on three goals: join with other parents to protect kids from becoming drug users, shut down headshops, and stop decriminalization. Some 3,000 parent groups from the mid-70s to the early 90s formed parent peer groups to protect their children and their children’s friends from using drugs. Many, usually in state capitals, became politically active. Their efforts to persuade legislators to pass laws outlawing drug paraphernalia drove the industry out of business. No more states decriminalized marijuana over the next several decades. NORML’s funding nosedived forcing the organization to severely curtail its decriminalization crusade.

Between 1978-79 and 1992, high school seniors’ marijuana use plummeted:

Lifetime use was cut nearly in half from 60.4 percent to 32.6 percent.

Past-year use dropped by more than half from 50.8 percent to 21.9 percent.

There was a three-fold decrease in past-month use, and a

five-fold decrease in daily marijuana use.

The first two directors of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Robert DuPont, MD, and William Pollin, MD, credit the Parent Movement with bringing about this significant reduction in marijuana use among adolescents. But in just four years, these gains reversed:

Seniors’ lifetime marijuana use rose from 32.6 percent in 1992 to 44.8 percent in 1996-1997.

Their past-year use nearly doubled over those four years, from 21.9 percent to 38.5 percent.

Past-month use among seniors did double, and

Daily use rose more than three-fold.

What made that happen?

Medical Marijuana

In 1992, three billionaires began pumping money into a by-then moribund NORML as well as into two new groups, the Marijuana Policy Project, and a coalition of other groups that became the Drug Policy Foundation. They targeted states that allow ballot initiatives, made unsubstantiated claims about the healing powers of marijuana, bought voters’ signatures, and placed measures to legalize marijuana as medicine on the ballots of states few lived in, leaving taxpayers to pay for the consequences of their actions. A steady stream of media stories across the nation educated children that pot is medicine and they responded in kind. If a government wouldn’t reduce penalties for a drug that could hurt you, that drug surely couldn’t hurt you if it was medicine! The national cacophony that led up to the first state legalizing pot as medicine – California in November 1996 – carried that message and kids heard it loud and clear.

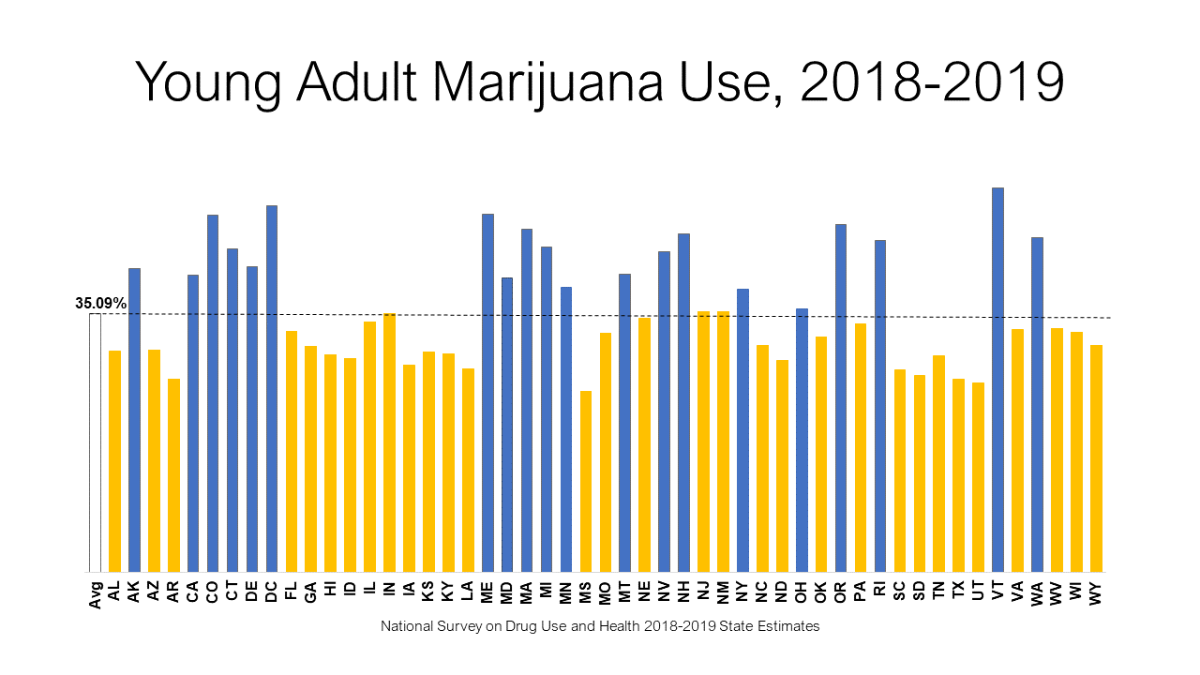

The National Household Survey on Drug Abuse shows much of these same patterns for both adolescents and young adults during the 70s, 80s, and 90s. But since that survey’s data cannot be compared to NSDUH’s, the best we can do is look at the most recent survey, which is the 2018-2019 state estimates. The following two charts are created on the same vertical axis of 0 percent to 60 percent. The first one shows past-year marijuana use among adolescents, the second among young adults.

No, not all of the blue bars are recreational states and yes, some of the yellow bars are. But 36 of these states have legalized marijuana for medical use and that has influenced young people ages 12 to 25 to engage in its use. Like decriminalization in the 70s, the novelty of turning pot into medicine with an intensive four-year campaign championed by national media has not only had a profound effect on the nation’s young people but also introduced a unique way to approve medicines by ballot-iinitiative and, later, legislative fiat rather than through the Food and Drug Administration. Should we worry that advocates are now applying that pattern to other drugs?

Access these graphics here.

Access YRBSS here.

Access NSDUH here.

Access MTF here.

Read National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of Methodological Studies, 1971-2014 [Internet] here.