Okanogan County Chief Criminal Deputy Steve Brown surveys the debris left over from an illegal pot farm that had masqueraded as a legal operation.

On a big-sky plateau on the eastern slope of the Cascades, a 10-acre parcel of land has been trashed by illicit pot farmers. Abandoned equipment rusts and jugs of chemicals molder.

Marijuana legalization wasn't supposed to look like this.

Five years into its experiment with legal, regulated cannabis, Washington state is finding that pot still attracts criminals.

Okanogan County Chief Criminal Deputy Steve Brown helped raid this farm last fall. What was striking, he says, is how brazen it was: located just off the road, within sight of neighbors. Before legalization, an operation like this would at least have been hidden up in the hills.

"Now it's just out in the open, because everywhere you drive in the county you see the fencing, and everybody just assumes it must be just another legal grow going on."

This particular grow was just a few hundred feet from licensed, state-regulated pot farms. Brown recalls how the growers tried to "blend in."

"They acted like it was legal," he says, and he says they even tried to fool the tax assessor, filing to pay agricultural property taxes at the rate for licensed pot growers.

After an investigation, it turned out the growers were part of a network with connections to California and Thailand, who had purchased six properties in the Okanogan area. They'd been growing pot illegally on five.

Law enforcement officers uproot a large-scale illegal marijuana grow, one of several masquerading as legal operations in Okanogan County.

Legalization was also supposed to end pot smuggling, but that hasn't worked out either.

Deputy Brown keeps track of the people from this area who've been arrested transporting big loads of marijuana through other states, such as Arkansas and Wyoming. At least one of them had ties to a licensed marijuana store in the Okanogan area, according to investigators.

The reason is simple economics. Overproduction in Washington and other states with legal pot, such as Oregon, has led to a market glut — and rock-bottom wholesale prices in the legal market.

Jeremy Moberg, of CannaSol Farms, shows the state-mandated tags that are meant to track all legal marijuana plants.

"You're going to get maybe $1,500 a pound — tops," says Jeremy Moberg. He runs a licensed outdoor marijuana farm in Okanogan called CannaSol. "And a lot of people in farms around here are going to be lucky to get $250 a pound."

In states where marijuana is still illegal, the same product would easily fetch three or four times that price, Moberg says. That's a powerful temptation for licensed farmers who aren't covering production costs right now.

"[For] those that are just totally underwater, and lost all their money, I think it's a huge incentive to think that they could divert [legally-grown pot to the black market]," Moberg says. But he says he wouldn't take that risk.

"I have a strong enough fear for prison and enforcement to not think about that too much," he says.

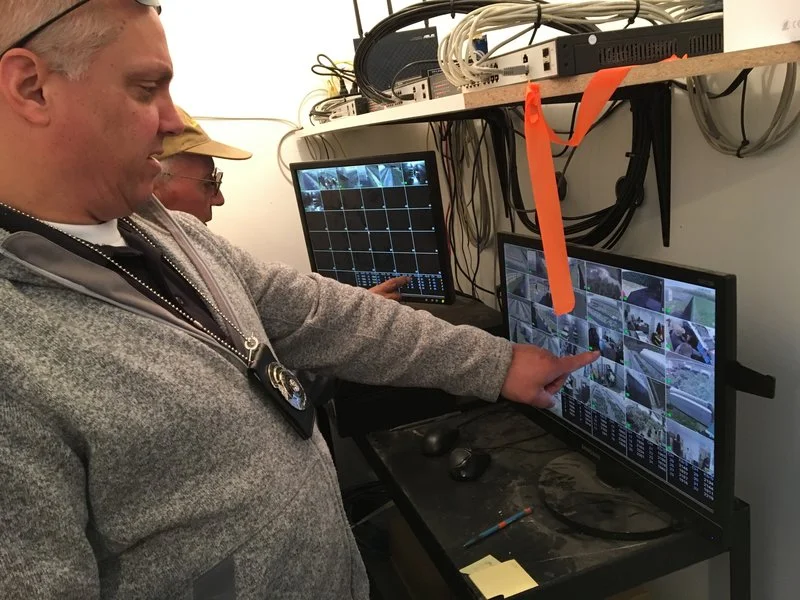

Officer Steve Morehead, of the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board, does a spot check on the required video surveillance system at a licensed pot grower near Brewster, on the Columbia River.

A couple of licensed farms nearby have been caught not keeping proper track of their marijuana. Another is accused of using marijuana to pay a contractor. That's a major violation of the state's tracking rules for legally-grown pot.

"I could see where it's definitely tempting for someone to take it out of state," says Steve Morehead, an enforcement officer for the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board. He does surprise inspections of licensed growers to make sure they're keeping all their marijuana inside the tracking system, meant to prevent diversion.

"Every plant that is 8 inches or taller needs to have a [bar-coded] tag on it," he says.

An illegal marijuana farm shielded from view with fencing that investigators believe was meant to mimic the fencing around legitimate pot farms.

But he acknowledges the system isn't foolproof, especially if someone decides to "set aside" some of the buds from those tagged plants.

"There is a lot of the honor system, of how many ounces or how many pounds did you take off these plants," he says. "We're trusting them to input good information."

This may be the Achilles' heel of Washington state's marijuana tracing system. "The amount of product that a plant produces depends on lots of different things, it's not a constant," says Mark Kleiman. He's a professor of public policy at New York University and his consulting company BOTEC studies the pot market for the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board.

"So it's certainly possible that someone could ship some out the back door," he says.

This matters for many reasons. Off-the-books pot feeds the glut, depressing prices further and tempting producers to sell more into the black market, tax-free.

Still, diversion is hard to prove, unless investigators are tipped off and know to check the thousands of hours of surveillance videos that licensed growers are required to keep.

Illegal grows are easier to catch. The Thai-California network operating in Okanogan was not unique.

Last November, law enforcement on the Washington coast said they'd discovered a large network of illegal marijuana grows run by Chinese nationals. Police in three counties served 50 search warrants, confiscated 32,000 pot plants, 26 vehicles and $400,000 in cash and gold. They also arrested 44 people.

Given the low wholesale prices in Washington, investigators believe the illegal grows are producing for other states where prices are higher, and are here simply to use the local legal pot industry as cover.

Raids like that are ominous for the supporters of Washington's regulated pot system. Organized crime and cross-border trafficking are just the problems that the Justice Department said states with legalized marijuana should keep a lid on. Such incidents could give the feds a reason to crack down on the state's licensed growers and retailers, which are still illegal in the eyes of federal law.

That worries licensed producers such as Moberg.

"If it's organized crime, building operations made to look like [legal grows], in order to export out, I'm much more concerned," he says. "Obviously this is what the feds are mostly concerned about. So if they are able to do this, and the attention is brought upon us that this is happening, then I don't think that is great for all of us."